When we left my island home for the last time, I wore slippers and my only pair of long pants on the plane. But Hawaii was not my parent’s home, and eventually, my family moved to a small town in Washington State where I was raised. We stayed in Hawaii for a few years, enabling me to spend my early childhood still a part of my island culture. I was adopted into a white family shortly after I was born. And not being able to process the myriad of conflicting feelings, I shoved it down and buried it beneath my awareness for later excavation. Somehow this experience would only compound the confusion I felt around my own identity. Upset and insulted they screamed, “She’s White! No, She’s Hawaiian!” Like the time my girlfriends vehemently defended me against someone who asked if I was Oriental. I would often find myself standing on the fence between cultures - not fully apart of one or the other- or denying one to embrace the other. It was part of a slow peeling of all that was deemed unnecessary and unfit for my new experience as a minority in a white world.īy the time I was in high school, though I no longer spoke Hawaiian Pidgin. Over time, my childhood tongue was slowly stripped away.

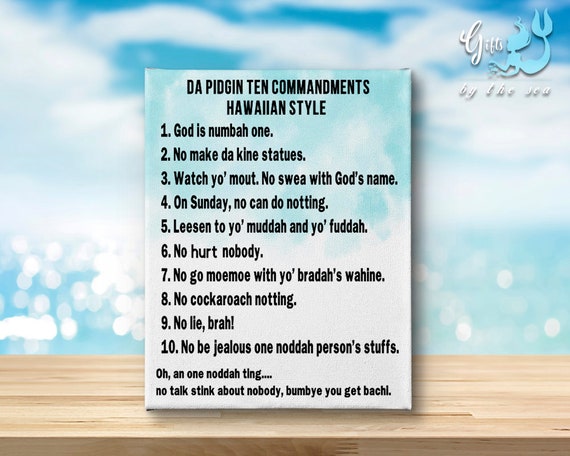

I’d been taught that Hawaiian Pidgin, the peculiar speech I had as a child, was just bad manners and nothing more than strange island slang, even though I could not make my most basic need to use the restroom understood to my teacher when I told her, “I needed to make shishi”. With a strange curiosity, like a dog sniffing the wind, I kept reading and moving closer, circling the words to re-read the phrase, “…and acquired by children as their first native language.” That’s when it hit me I never knew I had a native language. It was gently reminding me of something I had long forgotten.

I could feel this information subtly shifting and reworking something inside me. Strangely, I found myself reading this last line several times. According to Kent Sakoda, a lecturer in second languages at UH, “Pidgin became the primary language of many of those who grew up in Hawaii, and children began to acquire it as their first language.” Still uncomfortable mining my own memories, I continued on with my research. To my surprise, the Hawaiian Pidgin I spoke as a young girl was now an actual language listed by the US census. Hawaiian Pidgin: Discovering My Native Languageįor those unfamiliar with the Hawaiian Islands and its culture, Hawaiin Pidgin (or Hawaiian Creole English) is an English-based Creole language spoken in Hawaii.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)